Evolution is a fascinating subject. When, why and how do adaptations send species off in new directions to gain or surrender ascendancy?

I thought about evolution when I read about the historic electric motorcycle event at the Isle of Man TT, when Tony Rutter chalked up the first-ever 100mph racing lap of the 37.5-mile Mountain Circuit on a zero emission machine.

It took conventional racing bikes nearly 50 years to break the magic ton around the island but the battery bikes have only been trying since 2009. It’s as if EV technology is waking up from a long sleep.

Although we’re not far away from the second centenary of the first practical electric vehicle, EV evolution has certainly been in a state of suspended animation for most of the last 100 years.

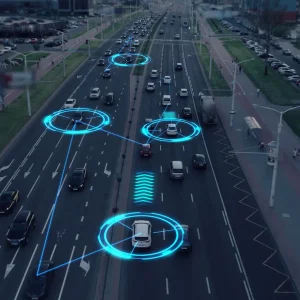

But thanks to modern technology and materials, the evolution of today’s electric vehicles is now proceeding incredibly quickly.

To many people, the question is ‘when will EVs be able to match the range of conventional cars?’ but that’s not necessarily how technical evolution works.

EVs can be seen as an emerging response to a variety of changes in the road transport environment. The expectation that liquid fossil fuels will be in critically short supply in a decade or two, for one thing, and concerns over local air quality in cities for another.

Unlike natural evolution, where species adaptations usually take millennia to have an effect on their surrounding environment, technical evolution often leads to rapid changes in the industrial landscape and people’s behaviours.

Look how quickly the railways and the Underground changed the way Londoners lived and worked in the 19th Century, for example.

Instead of waiting for EVs to adapt to business as usual motoring, the smart money could well be on those fleets and businesses that adapt the way they work to capitalise on the evolutionary opportunities inherent in the full range of technologies on offer – mobile communications, telecommuting, car-sharing, ultra-efficient conventional cars, and the coming second and third generation EVs.

And because the environment can change so fast, it’s not something fleets can afford to put off forever.

After all, the inability of the world’s liquid fossil fuel supply to climb off the bumpy plateau it’s been on since 2005 could plausibly do to distance-no-object mass motoring what the Chicxulub meteor impact did to the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

In that case, the companies that emerge as winners in the post-liquid landscape would be the ones that adapted their mobility strategies soonest.

Getting back to the Isle of Man, the electric bikes’ achievement does need to be put in context of conventional machines that lap the circuit at more than 130mph, for twice the distance before needing to refuel. E-bikes may never emulate that capability.

But then, the first mammals would have seemed fairly inconsequential alongside the dominant dinosaurs of their time – and look where we are now.

And, as Charles Darwin discovered, islands are definitely the right place to see evolution in action.

Follow BusinessCar on Twitter.